|

Tomorrow's spacecraft will be built using

advanced materials with mind-boggling properties.

by Patrick L. Barry

"What I'm really looking for," you say

to the salesman, "is a car that goes at least 10,000 miles between

fill-ups, repairs itself automatically, cruises at 500 mph, and weighs

only a few hundred pounds."

As he stands there wide-eyed, you add, "Oh yeah, and I can only

spend about a quarter of what these other cars cost."

A request like this is sure to get you laughed off the new-car

lot. But in many ways, this dream car is a metaphor for the space

vehicles we'll need to expand our exploration of the solar system

in the decades to come. These new spacecraft will need to be faster,

lighter, cheaper, more reliable, more durable, and more versatile,

all at the same time.

Impossible? Before you answer, consider how a rancher from 200 years

ago might have reacted if a man had asked to buy a horse that could

run 100 mph for hours on end, carry his entire family and all their

luggage, and sing his favourite songs to him all the while! Today

we call them minivans.

Revolutions in technology - like the Industrial Revolution that

replaced horses with cars - can make what seems impossible today

commonplace tomorrow.

Such a revolution is happening right now. Three of the fastest-growing

sciences of our day - biotech, nanotech, and information technology - are

converging to give scientists unprecedented control of matter on

the molecular scale. Emerging from this intellectual gold-rush is

a new class of materials with astounding properties that sound more

at home in a science fiction novel than on the laboratory workbench.

Imagine, for example, a substance with 100 times the strength of

steel, yet only 1/6 the weight; materials that instantly heal themselves

when punctured; surfaces that can "feel" the forces pressing on

them; wires and electronics as tiny as molecules; structural materials

that also generate and store electricity; and liquids that can instantly

switch to solid and back again at will. All of these materials exist

today ... and more are on the way.

more

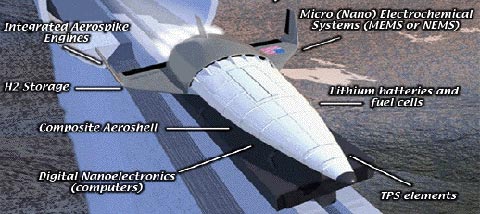

A

next-generation minivan? Advanced materials will be essential

for making dramatically improved spacecraft possible.

|

With such mind-boggling materials at hand, building

the better spacecraft starts to look not so far fetched after all.

The challenge of the next-generation

spacecraft hinges on a few primary issues. First and foremost, of

course, is cost.

"Even if all the technical obstacles were solved

today, exploring our solar system still needs to be affordable to

be practical," says Dr. Neville Marzwell, manager of Revolutionary

Aerospace Technology for NASA's Next Decadal Planning Team.

Lowering the cost of space flight primarily means reducing weight.

Each pound trimmed is a pound that won't need propulsion to escape

from Earth's gravity. Lighter spaceships can have smaller, more

efficient engines and less fuel. This, in turn, saves more weight,

thus creating a beneficial spiral of weight savings and cost reduction.

The challenge is to trim weight while increasing

safety, reliability, and functionality. Just leaving parts out won't

do.

Scientists are exploring a range of new technologies that could

help spacecraft slim down. For example, gossamer materials - which

are ultra-thin films - might be used for antennas or photovoltaic

panels in place of the bulkier components used today, or even for

vast solar sails that provide propulsion while massing only 4 to

6 grams per square meter.

Composite materials, like those used in carbon-fiber tennis rackets

and golf clubs, have already done much to help bring weight down

in aerospace designs without compromising strength. But a new form

of carbon called a "carbon nanotube" holds the promise of a dramatic

improvement over composites: The best composites have 3 or 4 times

the strength of steel by weight - for nanotubes, it's 600 times!

more

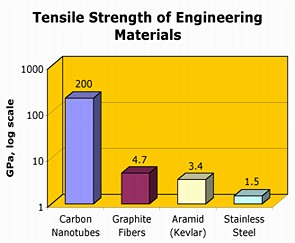

The tensile

strength of carbon nanotubes greatly exceeds that of other

high-strength materials. Note that each increment on the

vertical axis is a power of 10.

|

"This phenomenal strength comes from the

molecular structure of nanotubes," explains Dennis Bushnell, a chief

scientist at Langley Research Centre (LaRC), NASA's Centre of Excellence

for Structures and Materials. They look a bit like chicken-wire rolled

into a cylinder with carbon atoms sitting at each of the hexagons'

corners. Typically nanotubes are about 1.2 to 1.4 nanometers across

(a nanometer is one-billionth of a meter), which is only about 10

times the radius of the carbon atoms themselves.

Nanotubes were only discovered in 1991, but already the intense

interest in the scientific community has advanced our ability to

create and use nanotubes tremendously. Only 2 to 3 years ago, the

longest nanotubes that had been made were about 1000 nanometers

long (1 micron). Today, scientists are able to grow tubes as long

as 200 million nanometers (20 cm). Bushnell notes that there are

at least 56 labs around the world working to mass produce these

tiny tubes.

"Great strides are being made, so making bulk materials using nanotubes

will probably happen," Bushnell says. "What we don't know is how

much of this 600 times the strength of steel by weight will be manifest

in a bulk material. Still, nanotubes are our best bet."

Beyond merely being strong, nanotubes will likely be important

for another part of the spacecraft weight-loss plan: materials that

can serve more than just one function.

"We used to build structures that were just dumb, dead-weight holders

for active parts, such as sensors, processors, and instruments,"

Marzwell explains. "Now we don't need that. The holder can be an

integral, active part of the system."

Imagine that the body of a spacecraft could also store power, removing

the need for heavy batteries. Or that surfaces could bend themselves,

doing away with separate actuators. Or that circuitry could be embedded

directly into the body of the spacecraft. When materials can be

designed on the molecular scale such holistic structures become

possible.

Humans can feel even the slightest pinprick anywhere on their bodies.

It's an amazing bit of self-monitoring - possible because your skin

contains millions of microscopic nerve endings as well as nerves

to carry those signals to your brain.

Likewise, materials that make up critical systems in a spaceship

could be embedded with nanometer-scale sensors that constantly monitor

the materials' condition. If some part is starting to fail - that

is, it "feels bad" - these sensors could alert the central computer

before tragedy strikes.

Image courtesy NASA's Morphing Project at LaRC.

This piezoelectric

material, developed at NASA's Langley Research Centre (LaRC),

can "feel" deformations such as bending or surface pressure,

producing a small voltage in response that can act as a

signal for a central computer.

|

Molecular wires could carry the signals from

all of these in-woven sensors to the central computer, avoiding

the impractical bulk of millions and millions of today's wires.

Again, nanotubes may be able to serve this role. Conveniently, nanotubes

can act as either conductors or semi-conductors, depending on how

they're made. Scientists have made molecular wires of other elongated

molecules, some of which even naturally self-assemble into useful

configurations.

Your skin is also able to heal itself. Believe

it or not, some advanced materials can do the same thing. Self-healing

materials made of long-chain molecules called ionomers react to

a penetrating object such as a bullet by closing behind it. Spaceships

could use such skins because space is full of tiny projectiles - fast-moving

bits of debris from comets and asteroids. Should one of these sand-

to pebble-sized objects puncture the ship's armor, a layer of self-healing

material would keep the cabin airtight.

Meteoroids aren't the only hazard; space is filled with radiation,

too. Spaceships in low-Earth orbit are substantially protected by

our planet's magnetic field, which forms a safe bubble about 50,000

km wide centred on Earth. Beyond that distance, however, solar flares

and cosmic rays pose a threat to space travelers.

Scientists are still searching for

a good solution. The trick is to provide adequate shielding without

adding lots of extra weight to the spacecraft. Some lightweight

radiation-shielding materials are currently being tested in an experiment

called MISSE onboard the International Space Station. But these alone won't be

enough.

The real bad guy is Galactic Cosmic Radiation

(GCR) produced in distant supernova explosions. It consists, in

part, of very heavy positive ions - such as iron nuclei - zipping

along at great speed. The combination of high mass and high speed

makes these little atomic "cannon balls" very destructive. When

they pierce through the cells in people's bodies, they can smash

apart DNA, leading to illness and even cancer.

"It turns out that the worst materials you can use for shielding

against GCR are metals," Bushnell notes. When a galactic comic ray

hits a metallic atom, it can shatter the atom's nucleus - a process

akin to the fission that occurs in nuclear power plants. The secondary

radiation produced by these collisions can be worse than the GCR

that the metal was meant to shield.

Ironically, light elements like hydrogen

and helium are the best defence against these GCR brutes, because

collisions with them produce little secondary radiation. Some people

have suggested surrounding the living quarters of the ship with

a tank of liquid hydrogen. According to Bushnell, a layer of liquid

hydrogen 50 to 100 cm thick would provide adequate shielding. But

the tank and the cryogenic system is likely to be heavy and awkward.

A solar

flare blasts energetic radiation into space

|

Here again, nanotubes might be useful. A lattice

of carbon nanotubes can store hydrogen at high densities, and without

the need for extreme cold. So if our spacecraft of the future already

uses nanotubes as an ultra-lightweight structural material, could

those tubes also be loaded up with hydrogen to serve as radiation

shielding? Scientists are looking into the possibility.

Going one step further, layers of this

structural material could be laced with atoms of other elements

that are good at filtering out other forms of radiation: boron and

lithium to handle the neutrons, and aluminium to sop up electrons,

for example.

Earth's surface is mostly safe from cosmic radiation,

but other planets are not so lucky. Mars, for example, doesn't have

a strong global magnetic field to deflect radiation particles, and

its atmospheric blanket is 140 times thinner than Earth's. These

two differences make the radiation dose on the Martian surface about

one-third as intense as in unprotected open space. Future Mars explorers

will need radiation shielding.

"We can't take most of the materials with us

for a long-term shelter because of the weight consideration. So

one thing we're working on is how to make radiation-shielding materials

from the elements that we find there," says Sheila Thibeault, a

scientist at LaRC who specializes in radiation shielding.

One possible solution is "Mars bricks." Thibeault

explains: "Astronauts could produce radiation-resistant bricks from

materials available locally on Mars, and use them to build shelters."

They might, for example, combine the sand-like "regolith" that covers

the Martian surface with a polymer made on-site from carbon dioxide

and water, both abundant on the red planet. Zapping this mixture

with microwaves creates plastic-looking bricks that double as good

radiation shielding.

"By using microwaves, we can make these bricks quickly using very

little energy or equipment," she explains. "And the polymer we would

use adds to the radiation-shielding properties of the regolith."

Crafted

from smart materials, tomorrow's airplanes could have self-bending

wings that operate without flaps - thus reducing drag and

lowering fuel costs

|

Mars shelters would need the reliability of

self-sensing materials, the durability of self-healing materials,

and the weight savings of multi-functional materials. In other words,

a house on Mars and a good spacecraft need many of the same things.

All of these are being considered by researchers, Thibeault says.

Mind-boggling advanced materials will come in

handy on Earth, too.

"NASA's research is certainly focused

on aerospace vehicles," notes Anna McGowan, manager of NASA's Morphing

Project (an advanced materials research effort at the Langley Research

Centre). "However, the basic science could be used in many other

areas. There could be millions of spin-offs."

But not yet. Most advanced materials lack the

engineering refinement needed for a polished, robust product. They're

not ready for primetime. Even so, say researchers, it's only a matter

of time: Eventually that car salesman will stop laughing

... and start selling your space-age dream machine.

|