|

A

team of scientists has created the largest and most realistic simulation

to date of how our universe was formed.

by Chris Hale

Photo courtesy

of Carlos Frenk

Photo courtesy

of Carlos Frenk

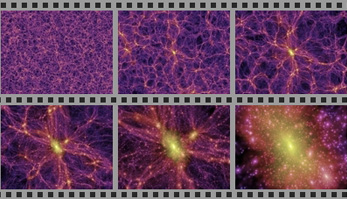

The Millennium

Simulation zooms in on a massive cluster of galaxies and

highlights its structure on different scales.

|

|

The universe is a very big place. It is crowded with billions of galaxies, an uncountable numbers of stars and a mysterious force called dark energy that is making it even bigger. In the last ten years, thanks to amazing images sent back by the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists have come up with a plausible explanation of how the universe began, starting with the Big Bang 13.7 million years ago and expanding into the stunning cosmos that exists today. But we are still far from fully understanding our universe and scientists are always looking for new tools to help them fill in the picture. One such tool is a model of the universe - inside a computer - recently created by scientists at the University of Durham in the U.K. Called the Millennium Simulation, it has been described as 'the largest and most realistic simulation ever of the growth of cosmic structure' and may help scientists unlock some of the elusive secrets of our universe.

How was the universe formed?

In the first few million years after the Big Bang, the universe was a dark, cold place full of swirling clouds of hydrogen and helium. But over billions of years, these gas clouds formed enormous galaxies made up of billions of stars. From these stars came all the scores of elements that our planet is made from - and which are also the building blocks of life. But how was all this complexity created?

At the University of Durham, physicist Carlos Frenk is testing out some important ideas about why the universe evolved the way it did. He is a member of the international team of scientists and programmers who created the Millennium Simulation. In particular, Frenk was interested in testing the role played by dark matter: a mysterious substance made from tiny particles that don't emit light that may make up 70% of the universe.

"Ordinary matter," says Frenk, "is made of atoms, particles that we're familiar with on Earth, protons, electrons, neutrons... [With] dark matter, although we don't yet know exactly what it is, we have every reason to believe it's a kind of elementary particle which is in essence different from ordinary matter. And that's why it doesn't shine, because it doesn't interact. It doesn't make atoms, it doesn't produce light."

Photo

courtesy of Carlos Frenk

Photo

courtesy of Carlos Frenk

From the

Millennium Simulation, the top image shows the galaxy distribution

for a rich cluster of galaxies whereas the bottom one shows

the corresponding dark matter distributions.

|

It's long been understood that if there was no dark matter exerting a powerful gravitational attraction, galaxies would simply fly apart like disintegrating wheels. But did this mysterious stuff have an even more important role to play in the evolution of the universe. Was it the invisible sculptor at work?

Frenk set himself a challenge. Could he programme the computers with the laws of physics, 10 billion particles of matter, plus a very big dollop of dark matter and get something that looked like the universe? After all, it's not possible - yet - to speed into the universe itself and set up a laboratory. The results of the experiment were a stunning success: perhaps best illustrated by the two galaxies shown here. One is 'real' - the other was made by the computer. It powerfully suggests that the model we have of how the universe evolved is right.

The universe as an expanding balloon

The story told by the Millennium Simulation is a spectacular one in which the very large is a consequence of the unimaginably small. The universe starts as a blazing fireball many times smaller than an atom and we can understand its structure by imagining an expanding balloon covered with spray paint. As the balloon expands, the paint cracks. Something similar happened early in the history of the universe: it wasn't born perfect. According to Frenk, the baby universe was born with a 'rash'. No one is quite sure why this happened but according to MIT physicist Max Tegmark: "One of the foundations of quantum physics, the laws that govern the micro-world, is the so-called Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which basically says in plain English that you can't have something completely uniform. And therefore, early on, when everything was tiny, there must have been these fluctuations."

As the universe stretches from a size smaller than an atom to thousands and then billions of miles across, these tears in its fabric are also stretched - think of the spray paint tearing ever wider on that balloon. After a few million years, the universe has become a dark, freezing place full of clouds of hydrogen and helium - plus a great deal of that mysterious dark matter. All this matter is spread across the universe in an uneven way by the primordial tears created by the Big Bang. It is at this moment that the dark matter really comes into its own. Its powerful gravitational pull starts sculpting the gas of ordinary atoms into what scientists call the cosmic web: it's this amazing process that is so beautifully shown by the Millennium Simulation. Inside the web, 'halos' of dark matter draw the gas into tighter and tighter clumps. The atoms of hydrogen, shoved together by the power of the dark matter, begin to heat - and eventually ignite as the first giant stars of the universe.

The final result is this: two galaxies. One is made by a computer. The other is 'real'. Can you tell them apart?

Frenk's conclusion is upbeat: "The galaxies generated in the simulation are almost indistinguishable from the real galaxies, and the similarity between the simulated and the real galaxy tells us that the assumptions that we have put into the simulation concerning how the Universe began, concerning the identity of the dark matter and concerning the laws of physics, that those assumptions provide a good description of what we see in nature. So the similarity between the virtual and the real galaxies are a nice confirmation of our cosmological model of the Universe."

For more information and to watch video of the simulation:

Millennium Simulation

http://www.mpa-garching.mpg.de/galform/press/

Millennium Simulation - The Largest Ever Model of the Universe

http://www.pparc.ac.uk/Nw/millennium_sim.asp

|