|

Forget Flowers!...Is Dopamine the main stimulus

for Romantic Love? Charles Pasternak explores the claims Helen Fisher

makes in her new book "Why

We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love".

by Charles

Pasternak

We mark the 14th of

February as St Valentine's Day - a lovers' festival since the 14th

century. Quite what a priest named Valentine, who suffered martyrdom

in Rome during the 3rd century, had to do with love is not at all

clear; if you look up St Valentine in the New Encyclopaedia Britannica

you will find reference only to the massacre, by Al Capone and his

cronies, of unarmed members of a bootlegging gang in Chicago on

the 14th of February 1929. Never mind. Love is what makes the world

go round, according to the 19th century French song, and this is

as good a time as any to consider just what the feeling of love

really is.

Emotions like love

are, according to clinical neurologist Antonio Damasio, 'neither

intangible nor elusive. Contrary to traditional scientific opinion,

feelings are just as cognitive as other percepts. They are the result

of a most curious physiological arrangement that has turned the

brain into the body's captive audience ... To discover that a particular

feeling depends on activity in a number of specific brain systems

interacting with a number of body organs does not diminish the status

of that feeling as a human phenomenon. Neither anguish nor the elation

that love or art can bring about are devalued by understanding some

of the myriad biological processes that make them what they are.

So what does Helen Fisher tell us about the science of love in her

latest book "Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic

Love"?

The crux of her argument is that hormones circulating in the brain

are the trigger:

"...this fire

in the mind is caused by elevated levels of either dopamine or norepinephrine

or both, as well as decreased levels of serotonin."

She supports her hypothesis

by mapping the areas of the brain that 'light up' by fMRI (functional

magnetic resonance imaging) when subjects who are passionately in

love are shown pictures of their adored one. The technique of fMRI

is essentially a scientific follow-up to the well-known reaction

we all experience when a personal comment gets too close: we blush.

The reddening of our face is due to increased blood flow below the

skin; fMRI localises areas of increased blood flow in the brain

when certain bundles of nerve cells respond to a particular stimulus:

raising an arm, being confronted by a frightening situation, concentrating

on a difficult mathematical calculation. Dr Fisher's contention

is that regions of the brain (the caudate nucleus and ventral tegmental

area in particular) in which the main chemical responsible for nerve

transmission is dopamine, are the ones that respond to the stimulus

of romantic love.

In order to recruit appropriate subjects to place inside an MRI

machine, Helen Fisher and her colleagues at the State University

of New York (SUNY) on the Stony Brook campus advertised for students

who had 'just fallen madly in love'. Once inside the machine, they

were shown a series of photographs (through an arrangement with

mirrors: the entire head is within the machine). Some photographs

were neutral, others were of their adored one. Between each picture

the brain was cleared of emotional responses by asking the subject

to mentally count backwards in increments of 7 from a large number

like 4,673.

The results - a correlation

between romantic love and the activity of dopamine-fired neurons

deep within the brain - astonished the author. I would like to share

her enthusiasm, but am constrained by the fact that no images of

caudate nucleus or ventral tegmental area glowing as volunteers

gaze in rapture at their William, Barbara or Bjorn are shown. There

is a 16 page Appendix detailing the ‘Being in Love’

questionnaire that each volunteer had to complete, but no glimmer

of an fMRI scan. We are assured that one of Dr Fisher's colleagues

'did many statistical analyses', but these are not presented either.

Instead we are referred merely to her recent publications. Neither

the Archives of Sexual Behavior nor Neuroendocronology Letters,

however, are likely to be found on the average reader's bookshelf.

I did not locate them in the extensive library of Imperial College

of Science, Technology and Medicine either.

Not that I doubt the

author's findings. They appear to be supported by independent work

of Semir Zeki and his colleagues at University College, London,

that predate the publications of the Fisher group by some two years.

What I am concerned about is Helen Fisher's implication that of

all the pleasurable emotions one might feel, it is romantic love

alone that causes one's dopaminergic neurons to work overtime. I

suspect that had she shown an 18 year old Carmelite nun pictures

of the Virgin Mary, the same result might have been obtained. Indeed

I am ready to jump into her brain scanner and have pictures of caviar

blinis flashed before my eyes, or excerpts from Schubert's String

Quintet in C relayed to my ears: I'll bet my caudate nucleus would

respond as well. In short, I believe that gazing at a picture of

your sweetheart is but one of thousands of pleasurable emotions

that are transmitted along dopaminergic pathways.

The blobs that light

up by fMRI may be no bigger than a pin head, but that still means

that each encompasses some million neurons (nerve cells), communicating

with as many as a thousand others. To establish the precise details

of this network - by methods not yet available - is a Herculean

task to which Dr Fisher does not allude. Instead she writes entertainingly

about topics such as lust (triggered by the hormone testosterone,

that inceases sexual drive in women as well as in men), rejection

and despair. Her story is peppered with quotations, from Aristotle

to Yeats, with more than twenty from Shakespeare alone. No doubt

we should be impressed by her literary erudition. Yet the Oxford

Dictionary of Quotations - that does find a place on my bookshelf

- contains over five hundred references to love, so Dr Fisher's

scholarly contribution is not, perhaps, so remarkable after all.

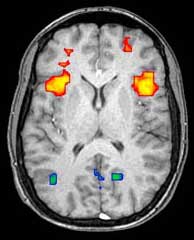

NIMH Laboratory of Brain and Cognition

An fMRI

scan investigating areas of the brain used in working memory

- Similar types of scans were carried out by Dr Fisher in

her research

|

On the other hand there

is no doubt that Helen Fisher writes with a light, breezy touch

and that she presents a comprehensive account of the various emotions

that interact with romantic love. So far as the underlying chemistry

is concerned, that too is presented in a clear manner. But it is

not chemistry that will reveal the working of the mind. No more

than fifty different types of molecule have so far been recognised

to function as neurotransmitters in the human body. Let me remind

you what these chemicals do. The connection between one nerve cell

and the next is a salt water-filled fibre that stops just short

of the nerve cell it is going to innervate. A tiny electric current,

generated in the first cell, passes along the fibre until it reaches

the gap between nerve fibre and the recipient cell. At this point

a chemical substance, the aptly named neurotransmitter, is released.

Neurotransmitter molecules bind to the membrane of the recipient

cell, causing it to respond in a particular manner. Within the brain,

the outcome is generally to transmit current to a further nerve

cell, and so on. There are over a trillion discrete fibers that

connect the hundred billion nerve cells in our brain to each other;

many nerve cells are linked to more than a thousand other cells.

The result is an immensely complicated neural network. No two brains,

not even those of identical twins, have exactly the same cell-to-cell

connections. With a trillion fibres and just fifty types of neurotransmitter

to choose from, it is clear that the vast majority of fibres use

the same neurotransmitter. So it is not chemicals like dopamine

or norepinephrine that distinguish one set of fibres from another.

The discrimination between thoughts of love and every other emotion

must reside in the precise pathways – among a myriad of possibilities

– that are followed when a new feeling, a novel thought, arises

in the brain.

So it is not chemistry but biophysics - or an innovative discipline

yet to be developed - that will elucidate the basis of emotions

like love and hate, calm and anger, pleasure and sorrow, joy and

despair. In the meantime we can do no more than applaud the author's

attempts, and look enviously across the Atlantic: what fun it must

be for a love-struck psychology student at Stony Brook to have the

opportunity of engaging in Helen Fisher's research projects.

[1] Antonio R Damasio: Descartes' Error.

Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain (Picador, London, 1995, p xv).

Available to Buy from Amazon.com

or Amazon.co.uk

[2] Helen Fisher: Why

We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love (Henry Holt and

Company, New York, 2004, £12.28/$25.00) Available to Buy from

Amazon.com

or Amazon.co.uk

|