|

Does

the future of robotics hold the promise of a dream come true to

lighten the workload on humanity and provide companionship. Or the

murder and mayhem of Hollywood movies?

by Dr Dylan Evans

When the Czech playwright

Karel Capek sat down in 1920 to write a play about

humanoid machines that turn against their creators, he decided to

call his imaginary creations 'robots', from the Czech word for 'slave

labour'. Ever since then, our thinking about robots, whether fictional

or real, has been dominated by the two key ideas in Capek's play.

Firstly, robots are supposed to do the boring and difficult jobs

that humans can't do or don't want to do. Secondly, robots are potentially

dangerous.

These two ideas remain

influential, but not everyone accepts them. The first dissenting

voice was that of the great Russian-American science-fiction writer,

Isaac Asimov, who was born the same year that Capek wrote his notorious

play. In 1940, barely two decades later, while others were still

slavishly reworking Capek's narrative about nasty robots taking

over the world, Asimov was already asking what practical steps humanity

might take to avoid this fate. And instead of assuming that robots

would be confined to boring and dangerous jobs, Asimov imaged a

future in which robots care for our children, and strike up friendships

with us.

From the perspective

of the early twenty-first century, it might seem that Capek was

right and that Asimov was an idealistic dreamer. After all, most

currently-existing robots are confined to doing nasty, boring and

dangerous jobs, right? Wrong. According to the 2003 World Robotics

Survey produced by the United Nations

Robot Arm

over Earth with Sunburst

|

Economic Commission for Europe,

over a third of all the robots in the world are designed not to

spray-paint cars or mow the lawn, but simply to entertain humans.

And the number is rising fast. It is quite possible, then, that

the killer app for robots will turn out to be not the slave labour

envisaged by Capek, but the social companionship imagined by Asimov.

AIBO

|

The most impressive

entertainment robot currently on the market is undoubtedly

the Aibo, a robotic dog produced by Sony. According to Onrobo.com,

a website devoted to home and entertainment robotics, Aibo is the

standard by which all other entertainment robots are measured. Special

software allows each Aibo to learn and develop its own unique personality

as it interacts with its owner. But at over a thousand pounds a

shot, they aren't cheap.

Commercial products

like the Aibo still have some way to go before they have the quasi-human

capacities of 'Robbie', the child-caring robot envisaged by Asimov

in one of his earliest short-stories, but the technology is moving

fast. Scientists around the world are already beginning to develop

the components for more advanced sociable robots, such as emotional

recognition systems and emotional expression systems.

Emotions are vital

to human interaction, so any robot that has to interact naturally

with a human will need to be able to recognise human expressions

of emotion and to express its own emotions in ways that humans can

recognise. One of the pioneers in this area of research (which is

known as 'affective computing') is Cynthia Breazeal, a roboticist

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has built an emotionally-expressive

humanoid head called Kismet. Kismet has moveable eyelids, eyes and

lips which allow him to make a variety of emotional expressions.

When left alone, Kismet looks sad, but when he detects a human face

he smiles, inviting attention. If the carer moves too fast, a look

of fear warns that something is wrong. Human parents who play with

Kismet cannot help but respond sympathetically to these simple forms

of emotional behaviour.

Another emotionally-expressive

robot called WE-4R has been built by Atsuo Takanishi and colleagues

at Waseda University in Japan. Whereas Kismet is limited to facial

expressions and head movements, WE-4R can also move its torso and

wave its arms around to express its emotions.

The gap between science

fiction and science fact is closing, and closing fast. In fact,

the technology is advancing so quickly that some people are already

worried about what will happen when robots become as emotional as

we are. Will they turn against their creators, as Capek predicted?

In the new Hollywood blockbuster, I, Robot (which is loosely based

on an eponymous collection of Asimov's short stories), Will Smith

plays a detective investigating the murder of a famous scientist.

Despite the fail-safe mechanism built into the robots, which prevents

them from harming humans, the detective suspects that the scientist

was killed by a robot. His investigation leads him to discover an

even more serious threat to the human race.

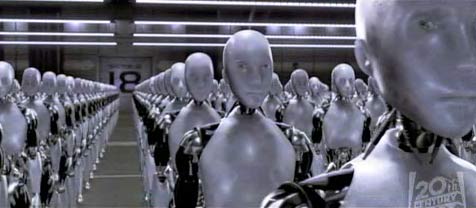

I,

Robot is set in the year 2035, thirty one years in the future.

To get an idea of how advanced robots will be by then, think about

how far videogames have come in the last thirty one years. Back

in 1973, the most advanced videogame was Pong, in which a white

dot representing a tennis ball was batted back and forth across

a black screen. The players moved the bats up and down by turning

the knobs on the game console. By today's standards, the game was

incredibly primitive. That's how today's robots will look to people

in the year 2035.

iRobots

from the film

|

Will those future people

look back at the primitive robots of 2004 and wish they hadn't advanced

any further? If we want to avoid the nightmare scenario of a battle

between humans and robots, we should start thinking about how to

ensure that robots remain safe even when they are more intelligent.

Isaac Asimov suggested that we could make sure robots don't become

dangerous by programming them to follow the following 'Three

Robot Laws':

1. A

robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a

human

being to come to harm.

2. A

robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such

orders

would conflict with the First Law.

3.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection

does not

conflict with the First or Second Law.

At first blush, these

three laws might seem like a good way to keep robots in

their place. But to a roboticist they pose more problems than they

solve. Asimov was well aware of this, and many of his short stories

revolve around the contradictions and dilemmas implicit in the three

laws.

The sobering conclusion

that emerges from these stories is that preventing intelligent robots

from harming humans will require something much more complex than

simply programming them to follow the three laws.

Note on the Author:

Dr Dylan Evans teaches robotics at the University of the West of

England, Bristol.

|